Portland and the Barrington family

The development and history of the Portland farm and the story of its founder, Henry Frederick Francis Adair Barrington

The issue of farming in Knysna has been fraught since the earliest days, both because of natural conditions in the area (soil, weather), and because of access to markets.

The story of the Barrington family of Portland, near Rheenendal, illustrates these challenges – and provides an insight into settler life in Knysna in the 19th century.

Portland farm was acquired by George Rex some time after his arrival in Knysna in 1804. A notary public (lawyer) and Registrar of the Courts Martial at the Cape Colony during the British occupation of 1795 – 1803, Rex sold his home in Cape Town when the Dutch took over the administration of the colony, and moved to Springfield Farm, between Knysna and Plettenberg Bay, which he’d acquired some years before by Crown Grant (the process by which government land was transferred to individuals at that time).

Shortly after arriving in the Southern Cape, Rex bought the farm Melkhoutkraal – which was lying derelict after having been sacked during the troubles on the Eastern Frontier – and set about establishing his homestead there, on the eastern shore of the Knysna Lagoon (Melkhoutkraal is now the Industrial Area, the Knysna Golf Course, and various neighbouring suburbs). In quick succession, he would also acquire the farms Uitzicht (on the western shore) from one Hendrik Barnard – splitting it into two portions which he named Belvidere and Brenton – and also Welbedacht, Sandkraal, and De Poort, which he renamed Eastford, Westford, and Portland.

These acquisitions gave Rex ownership of about 25,000 acres (10,100 hectares) of land around the lagoon: effectively, he owned the entire Knysna River basin.

Having arrived in the area with some means, Rex became a wealthy slave owner with thriving timber, trading, and shipping businesses – the ships to transfer the yellowwood, stinkwood, and other timber harvested for him in the local indigenous forests. (See ‘Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century’ on this site)

The Scottish Lieutenant, later Captain, Thomas Henry Duthie of the 72nd Highland Regiment – who was working as a superintendent on the construction of Sir Lowry’s Pass over the Helderberg Mountains from Somerset West to the Elgin Valley – visited Rex at Melkhoutkraal in 1830, and fell immediately in love with Rex’s 17-year-old daughter, Caroline. Their courtship lasted three years, and they married in 1883. Duthie then resigned his post, and bought the farm Belvidere from his father-in-law. (Duthie would later lay out the village of Belvidere – now Old Belvidere – and build the now famous Holy Trinity Church, consecrated 1855, with the help of Henry Barrington of Portland, and William Newdigate, who married Duthie’s eldest daughter, also named Caroline, and settled at Forest Hall in Plettenberg Bay. Thomas Duthie is significant to this story because, after meeting Henry Barrington by chance in George, Duthie invited him to visit Belvidere – which led to Barrington buying Portland from him, and settling in the area.)

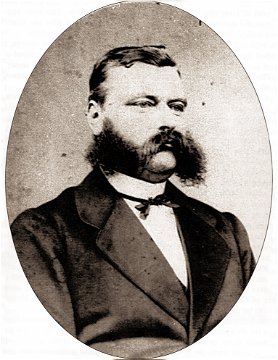

Henry Frederick Francis Adair Barrington

Henry Barrington was born to a wealthy family in Berkshire in the south of England on 28 July 1808. He attended the elite Charterhouse School, and then earned a law degree at Christ Church, Oxford. He became a barrister at the London Bar, but, finding the work not to his liking, joined the diplomatic corps and accepted a posting to Greece. This, too, was unsuitable, and by the age of 30, Barrington found himself briefly in South Africa.

During his second journey to the country (in 1842), he argued with Captain Jacobs, the commander of the ship on which he was travelling. He felt that Jacobs was making unwelcome passes at one of the women on board, and challenged him to a duel, which they fought with pistols after their arrival in Cape Town. Although Barrington was seriously wounded in the encounter, he recovered, and, once rested, set out for the Garden Route and his fateful meeting with Duthie.

Shortly after arriving in Knysna, Barrington bought the 2,188 ha Portland farm from Duthie for £400, and later acquired the neighbouring farm, now known as Karawater, to bring his total landholdings to a little over 5,000 hectares.

Portland, on the banks of the upper reaches of the Knysna River, was situated about 20 km from the village of Melville (now Knysna) via the Phantom Pass.

The friendship between Barrington and Duthie grew, and Barrington stayed with Duthie at Belvidere while building a 3-roomed house for himself at Portland.

In 1848, Barrington again returned to England – this time meeting Georgiana Knox (a great beauty known as the Belle of Bath), whom he would marry, and who would bear him three sons and four daughters (more about them later).

Back in the Cape, Barrington involved himself in legal work once more. In 1855 he was appointed chairman of the Board of Magistrates in the unfortunately named administrative region of British Kaffraria (headquartered in King Williamstown), which had been established in 1847 when the colonial government annexed the Ciskei between the Keiskamma and Great Kei rivers in the present-day Eastern Cape Province.

Board of Magistrates

The Board of Magistrates was to have been made up of magistrates attached to the local chiefs in the area – one per chief. Although it was never actually constituted, Barrington was the only qualified lawyer in the territory, and he was appointed to the post anyway. His duties included reviewing judgements, acting as resident magistrate and special magistrate, providing legal opinions, developing court procedures, drafting a standard labour contract, establishing a deeds office, and providing many other, related services.

Barrington’s period of office occurred during the time of the Great Cattle Killing of 1856-57, which came about as a result of the prophecies of Nongqawuse (c. 1841 – 1898), who foresaw a time when the Europeans would be expelled from the land if the Xhosa slaughtered all their cattle and destroyed their grain crops. This led to famine and disorder in the territory, and to a huge increase in crime, and, in turn, to Governor Sir George Grey taking advantage of the so-called ‘Chief’s Plot’ to destroy Xhosa nationality, and replace the black farmers of the region with whites. His Proclamation of 3 March, 1857 – which imposed the death sentence on anyone caught carrying arms during a robbery – was increasingly improperly enforced, and many local chiefs were brought up on trumped-up charges, leading to their imprisonment on Robben Island.

All of this appears to have worked on Barrington’s conscience, and he resigned from the service in 1859 (he was offered another, similar post – and refused it – in the following year. The Governor of the Cape Colony was recalled in 1861, and British Kaffraria was incorporated into the Colony in 1867 and, as it was no longer a separate administrative region, its unlamented name passed into history.)

The Great Fire of 1869

In 1860, Barrington began building a suitable manor house for the farm. It contained many large rooms filled with furniture imported from England, and an enormous library stocked with numerous books, including many legal volumes as befitted his profession.

On the 9th of February, 1869, though – just a few months after the building’s completion – a fire of unimaginable proportions swept through the farm and the entire district from Swellendam to Humansdorp, destroying everything in its path.

This was the Great Fire of 1869.

On 13 February, Barrington wrote in his diary: “My God! to what a state we are now reduced. My poor wife, myself, my 3 sons & my 4 dear daughters ... I have lost the labour & collections of a life, all my nice library but a dozen odd volumes ... I must learn to live here as a pauper & retrieve thereby what I can for my family ... All my selfish earthly hopes of a pleasant life & comfortable are gone & I have only to look to the society & goodness of my children & wife.”

Some sources credit Barrington with starting the blaze – he had, indeed, burned one of his lands just two days before – but the evidence against such an accusation is clear. For a detailed discussion about the case, see our page on this site, The Great Fire of 1869.

Despite his bleak outlook in the days following the fire, Barrington set about rebuilding his homestead almost immediately.

House of Assembly

Barrington accepted a nomination for, and was elected to, the Cape Colony’s House of Assembly, where he represented the district of George from 1870 to 1873.

During his time in the Cape and in King Williamstown, Georgiana stayed behind at Portland to manage the farm with the help of George Currey, a family friend (whose grave lies at the entrance to the churchyard of St. George’s in Knysna) – although she did spend some welcome time with her husband when he was stationed in King Williamstown (this would prove to be one of the few occasions when she was able to conduct a busy social life of her own).

Farming activities

Barrington tried numerous different farming activities at Portland:

- He built the Lawnwood Dam and a 5 kilometre long stone furrow to feed a water-driven sawmill that he installed to process the timber he harvested from his farms. This was the first mechanical sawmill in the area – previously, timber was cut into slabs by hand in two-man sawpits – but the project wasn’t commercially successful because of the distance to markets;

- He tried beekeeping, but he found the local bees to be ‘indolent.’ Wanting busier bees, he imported some from England – but they didn’t take to local conditions, and quickly died;

- He planted groves of mulberries in order to establish a silk farming operation – but those trees that did survive were destroyed in the Great Fire, and anyway the silkworms weren’t suited to the local climate, and they died, too;

- He planted apples for cider, and even imported a cider press – and then found that there was no market for cider in the Cape;

- He imported machinery for pearling barley – but found there was no market for that, either;

- He tried planting tobacco, but local conditions again proved unfavourable; and

- His cattle, sheep, and vegetable farming efforts proved only sufficient to feed his household’s needs.

On top of all of this, Barrington and his family had to put up with all the challenges of living in a quite wild part of the country. Besides numerous encounters with leopards (he called them ‘tigers’), there were also the ever-present elephants which roamed freely in the area – and, in fact, Barrington’s son, Hal, was said to have been trapped up a tree and ‘kept there for two days and a night’ by one of them.

Taskmaster

Despite the fact that he involved himself in various good works – he lobbied for the construction of what’s now known as the Seven Passes Road, the first reliable link between George and Knysna (which was only built after his death), and he built a church and school with a house for a teacher, and also contributed to the salary of the clergyman who came from Melville (now Knysna) to conduct services – Barrington was known as a hard taskmaster. All the men who came out from Britain with him to work for him eventually left his employ, and even his sons felt they were nothing more than unpaid labourers on the farm, and left as soon as they could. And his daughters (and, to an extent, his wife) complained that he did not allow them any social life, and would never allow them to attend any of the local parties or social occasions.

Henry Barrington died on the 25th of March, 1882. His wife, Georgiana, left the Cape Colony shortly after his death, never to return.

Portland house was redeveloped as a country hotel in the early 2000s, and now operates as Portland Manor.

Georgiana Barrington née Knox

Georgiana’s father, Colonel J.E. Wright Knox of the 87th Regiment, was not impressed when Henry Barrington proposed to his daughter in 1848: he didn’t want her – ‘the Belle of Bath’ – “going out to the colonies,” where he felt she’d live a hard life devoid of polite society. Nevertheless, Georgiana did accept Henry’s proposal, and they arrived at Plettenberg Bay at the end of that same year – together with an enormous cargo of wedding gifts, family heirlooms, furniture, and farming equipment. (Despite her assurances that she was “happy in Outeniqualand,” her family would continue pressing her to “leave that horrid land” and return to England for many years to come).

Georgiana’s first children were born at Portland: John in 1849; Henry Robert Shute (known as ‘Hal’) in 1852, and Florina Elizabeth Jane (‘Flos’) in 1853. Georgiana returned to England for the birth of her fourth child, William Gordon Samuel (b. 1855), after which she came home to South Africa; she then went back to Bath for the birth of Katharine Caroline (‘Kate,’ b. 1861), while both Idonea Maria (‘Imar’, b. 1863) and Gabriella Carlotta (b. 1869) were born in the Colony - Imar in Knysna, and Gabriella in George.

The privations of life on the farm combined with Henry’s stern behaviour must have affected the marriage, and her later letters, and his later diary entries, lack the love and joy of their earlier correspondence. Indeed, some of Henry’s notes are quite scathing of Georgiana’s housekeeping abilities. On 23 January, 1875, for example, he wrote: “she is quite incapable of understanding anything; all her affairs are haphazard & the suggestions of the moment; the silver discoloured, the knives blunt as soon as sharpened; the fuel left to the discretion of the servant, but continual scrubbings, and nothing I fancy thought of, & everything I object to done."

As we have seen, Georgiana did return to live in England, but only after the death of her husband. She was 58 years of age at the time, and took her four daughters with her. Although Kate, Imar, and Gabrielle would later return to South Africa, Flos remained with their mother and never married. Barrington had created an £8,000 trust for his wife at the time of their marriage, giving her life-long right to the income from the capital. She lived on this, and on the proceeds of a £25 bequest that she received on his passing, until her death in 1909.

Barrington's children: John Wildman Shute Barrington b. 17 November, 1849

Like his brother Hal, John attended school in England. After his return home, he formed the Portland Diamond Co., and left for the diamond fields of Kimberly, where he was unsuccessful. He then tried prospecting for gold in Pilgrim’s Rest, also unsuccessfully. In 1877, he returned to Portland and worked on the farm for most of the rest of his life, earning most of his income from milling the timber he harvested from Lawnwood farm. He remained a bachelor (his sister, Kate, returned to Portland to keep house for him), and was active in the social life of the district, joining the Knysna Rangers for the defence of the town during the South African War.

He died on 23 September, 1901.

Hal (Henry Robert Shute Barrington) b. 12 June, 1852

When John left for Kimberly, his brothers Hal and Will remained on the farm, working as labourers – milking, tending to the horses and the gardens, digging, reaping, and threshing, although Will tended to spend more time on his own farm, Karawater, which Henry had purchased for him.

When John returned to Portland in the style of the prodigal son in 1877, Hal became resentful, feeling that he’d remained behind to do all the hard work and keep the farm going while John had been off adventuring, and their father had spent his time in the Cape Parliament. Consequently, Hal volunteered for military service in the Zulu War (it seems he saw action at Rorke’s Drift), and although he returned to Portland soon after, his relations with his father soured to the point where Henry disinherited him, and he left for Kimberly and the diamond fields, never to return permanently to Portland or the Knysna district.

Hal married Maria Magdalena Pietersen in Kimberley 1882, and went to work for her brother, Stephanus, on one of his farms near Frankfort in the Free State. The couple had three children: Georgiana (b. 1885), Elizabeth (b. 1889), and Pieter Hendrik (b. 1896).

With the outbreak of the South African War, Hal joined the Frankfort Commando, fighting on the side of the Free State Republic, but he was caught and sent to a prison-of-war camp in Ceylon.

In 1900, their farm was sacked under Lord Kitchener’s Scorched Earth Policy. Maria, Elizabeth, and Georgiana were all raped, and they, together with young Pieter, were interned in one of the British concentration camps. Maria, Elizabeth, and Georgiana all died shortly after their release, and Pieter was adopted by his uncle.

On his own release, Hal returned to Frankfort, but found nothing left for him there. He then went prospecting in Australia, New Zealand, South America, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Colorado, British Columbia, and the Yukon. In all this time he visited Frankfort only once – in 1908 (the last time young Pieter would ever see him) – and he died a pauper in Johannesburg in 1919.

Will (William Gordon Samuel Barrington) b. 24 November, 1855

Although his brothers were sent to school in England, Will had to make do with staying behind at Portland because his father couldn’t afford the expense. Nevertheless, Henry bought the farm Karawater for him when the boy was just 16, and he farmed there, even though he didn’t have much: according to Henry’s diary entry of 1 January, 1879, “he has only a little ploughing to depend upon and an ostrich” – while on the 11th of January, he wrote that everyone was preparing for a gold rush at the Millwood Goldfields, and that the boy “hopes to make his fortune selling his maize and beans and transport riding with my wagon and oxen.”

After his father’s death, Will took on a partner (a Swede named Carlson), to help him with the farm. They began with ostriches, and bought 100 of them in Oudtshoorn – but 90 of them died in the first year, probably as a result of the inappropriate climate; they then tried both dairy and agricultural crops, but found that they were situated too far from the markets to make either of them pay. Eventually, Carlson left to work with Frank Newdigate at Forest Hall outside Plettenberg Bay, and Will sold Karawter in 1894.

In 1896 Will married Emily Montagu, daughter of John Montagu, Colonial Secretary of the Cape Colony, and they emigrated to Vancouver. They had no children. Will returned alone to South Africa and died in George in 1931, leaving his considerable estate in trust to his sisters, with the capital going to the George Hospital on their deaths.

Flos (Florina Elizabeth Jane Barrington) b. 27 November, 1853

Not much has been recorded about Flos in any of the three main sources about the Barrington family – Barrington’s own diary, letters between members of the family, or the writings of her sister, Katharine – although we do know that she remained at her mother’s side, unmarried, until Georgiana’s death.

Flos, Kate, Imar and Gabrielle had the benefit of an excellent governess – Emilie Ritchie – who looked after them at Portland from 1875. She installed “English discipline” to the household, and was so appreciated that, when Henry was looking for ways to cut costs, he made it clear that her salary was not to be tampered with. Although Emilie returned to England in 1877, she later came back to South Africa to teach at Diocesian School for Girls (DSG) in Makhanda (Grahamstown), where she eventually became head-mistress.

Kate (Katharine Caroline Barrington) b. 19 May, 1861

Kate met and married Frank, eldest son of William Henry Newdigate of Forest Hall in The Crags near Plettenberg Bay – but since her brother, John, disapproved of the relationship, the couple left to marry in Cape Town in 1890. Although they returned to live at Portland, the arrangement was uncomfortable, and Kate and Frank moved back to Forest Hall, where Frank set up a sawmill.

Kate and Frank had five children: Eleanor Imar (Bunny), Dot (Katherine), Francis, Henry, and John.

In 1899, Frank joined the Medical Corps attached to General Warren’s forces, but he was killed in action while tending to the wounded in a skirmish near Douglas in the Northern Cape. He never met his youngest son.

Kate inherited Frank’s share of the Newdigate properties in Plett, and would also inherit John’s estate (John died in 1900) – which included Portland and the other Barrington farms: Lawnwood, Redlands, and Sedgefield. She continued to farm and sell timber from Lawnwood, and married Lt. Col. James Meredith Maurice, who had commanded the garrison at Knysna during the South African War, and who lived at Portland until his death in 1936 – just 9 days before his wife’s own passing. (He was a somewhat pompous man whose step children never liked him.)

Imar (Idonea Maria Barrington) b. 22 August, 1863

Imar married Lindsay Ashley Foakes in 1896, at the age of 32. Foakes was a sailor and friend of the polar explorer Robert Scott (although he didn’t join Scott’s Antarctic expeditions, he was apparently involved in their planning).

Foakes retired from the Royal Navy at 45, accepted the post of Naval Advisor to England’s Postmaster General, and received an OBE in 1919. He then retired for the second time – with Imar – to Knysna in 1925, where he built the house, ‘Mountjoy’ at the top of Queen Street. He served as mayor of the town six times between 1927 and 1947.

Imar ded on 13 February, 1945, and Foakes died on 6 October, 1947.

Gabrielle (Gabriella Carlotta Barrington) b. 13 February, 1869

Gabrielle married John Hardy Stewart, an employee of the Forest Department, in 1909. The couple moved to Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), but Gabrielle later returned to Knysna alone – possibly following a divorce. She lived here, in the old Art Centre building in Queen Street, until her death on 19 August, 1946.

SOURCES

- Hatchuel, M.: ‘Now if you’ll look to your left… A Handbook for Tourist & Community Guides In Knysna and Plettenberg Bay’ The Garden Route & Klein Karoo Regional Tourism Organisation, George, 1998 (Revised 2001)

- Newdigate, James: ‘The Portland People The Story of a Settler Family,’ H.J. Newdigate, Knysna, 2006

- Newdigate, Katharine: ‘Honey, Silk and Cider A Life Portrait of Henry Barrington,’ A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1956

- Nimmo, Arthur: ‘The Knysna Story,’ Juta & Company, Cape Town, 1976

- Parkes, Margaret & Williams, V.M.: ‘Knysna the Forgotten Port,’ Emu, Knysna, 1988

- Storrar, Patricia: ‘A Vista and a Vision The Story of Belvidere, Knysna,’ Rutherford Publications, Knysna, 1993

- Tapson, Winifred: ‘Timber and Tides The story of Knysna and Plettenberg Bay,’ General Litho, Johannesburg, 1967

Author

This article in the series 'Our Recent Past' was written for the Knysna Museum by Martin Hatchuel - July, 2022

Share This Page