Gold mining: Knysna's Millwood gold fields

The story of the Millwood gold fields (in the forests northwest of Knysna) in the context of gold mining in Southern Africa

Knysna’s goldfields: the forest find that became a gold rush

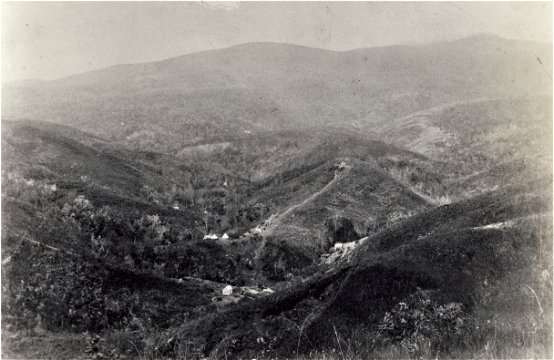

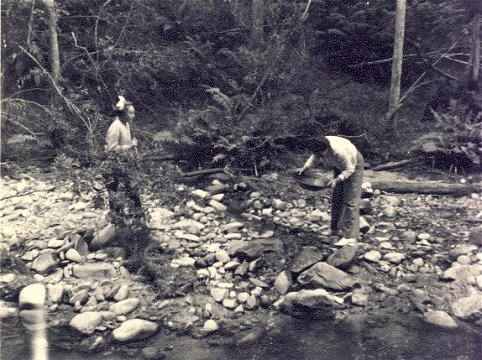

The area around Jubilee Creek, in the evergreen forests north-west of Knysna, became the site of a busy little mining town some years before the famous goldfields of the Witwatersrand were even discovered.

Knysna, though, wasn’t the first small town in South Africa to feel the excitement of gold - nor should the discoveries of the colonial era have come as a surprise, since various indigenous societies had been trading in the precious metal as far back as a thousand years ago.

Early history of gold in Southern Africa

PRE-COLONIAL PERIOD: The Mapungubwe Rhino - a tiny statue that would fit in the palm of your hand, and that was unearthed by archaeologists in 1932 - is probably the most famous symbol of the significance of gold for pre-colonial communities in the sub-continent.

This gold-covered, wooden artefact comes from the Kingdom of Mapungubwe, which thrived at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, in the present-day Mapungubwe National Park, between about 1075 and 1220 C.E.

According to Wikipedia, “The kingdom [of Mapungubwe] was the first stage in a development that would culminate in the creation of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century, and with gold trading links to Rhapta and Kilwa Kisiwani on the African east coast.”

“Together with Great Zimbabwe and Thulamela [in the present-day Kruger National Park], Mapungubwe formed part of a complex trading culture through which the gold of Africa reached Arabia, India and Phoenicia.” (pilgrims-rest.co.za)

SABIE & PILGRIM’S REST: The little tourist town of Pilgrim’s Rest in Mpumalanga saw a brief boom - and South Africa’s first modern-era gold rush - in the 1870s.

Although various people had found traces of gold in the region in the years between 1849 and 1870, the first payable gold deposits were found near the town of Sabie in an area officially registered as the New Caledonian Goldfields - but which quickly became known as the MacMac diggings (a nickname given them by Thomas François Burgers, President of the Transvaal Republic from 1871 to 1877).

One of the diggers, Alec ‘Wheelbarrow’ Patterson, found alluvial deposits in a stream that would later be named Pilgrims Creek. (‘Wheelbarrow’ got his own nickname after he ditched his donkey - which had kicked and hurt him - for a barrow, loaded it with his kit, and pushed it 1,600 km from Cape Town to MacMac).

Although Patterson kept his find secret, a second digger, William Trafford, didn’t: Trafford registered a claim of his own on a portion of Pilgrim’s Creek with the gold commissioner at MacMac. And when news of his claim got out, it triggered the biggest gold rush of the era.

Pilgrim's Rest was proclaimed a gold field on 22 September 1873, and by January 1874, when the gold commissioner, Major J.W. Angus MacDonald, moved his office from MacMac to Pilgrim's Rest, the diggings had attracted around 1,500 diggers, who were working about 4,000 claims in and around Pilgrim's Creek.

The creek’s alluvial gold began to run out by the beginning of the 1880s, though, and most of the independent diggers turned their focus to the newly discovered gold deposits in Barberton. Still, the MacMac diggings had attracted significant capital investment, and with the arrival of larger industrial equipment, the mining companies began to dig for gold-bearing ore. In 1895, a number of these companies amalgamated to form the Transvaal Gold Mining Estates (T.G.M.E.).

BARBERTON: The prospector Tom McLachlan discovered alluvial gold at Jamestown near Barberton, in the present-day Mpumalanga, in 1881, but, since the find was small and the area was rife with malaria (at that time an almost untreatable disease), very few people showed any interest. This changed, though, when Auguste ‘French Bob’ Roberts discovered an even richer deposit in the nearby Concession Creek on 20 June 1883.

Barberton thrived briefly as a gold mining region, but it was soon overshadowed by the opening of the reefs of the Witwatersrand.

Gold mining continues on a much reduced scale in the Barberton area to this day.

WITWATERSRAND: The English miner, J.H. Davis, is credited with the earliest find on the Witwatersrand - on the farm Pardekraal in 1852.

“He sold £600 of gold to the Transvaal Treasury and was subsequently ordered to leave the country. Another find by Pieter Jacob Marais was recorded in 1853 on the Jukskei River, but was subject to similar secrecy.” (Wikipedia)

In June 1884, the explorer and prospector Jan Gerrit Bantjes (who’d worked the area since the early 1880s) discovered the Witwatersrand’s first significant gold-bearing reef on the farm Vogelstruisfontein, while in September of that same year, the brothers Fred and Harry Struben found the Confidence Reef on the farm Wilgespruit, near Roodepoort. (The Strubens would later import the Rand’s first stamp mill, and install it at the Confidence Reef Mine. Made by Sandycroft Foundry in England, the mill was powered by an 8 horse-power Simms & Jefferies steam engine - also of British manufacture.)

Both Bantjes’ and the Strubens’ achievements were overshadowed, though, when George Harrison discovered the Witwatersrand’s main reef on the farm Langlaagte in July, 1886.

Harrison’s discovery went on to ignite the world’s largest gold rush - “Before long opencast workings were being opened up along the full length of the main reef in the present district of Johannesburg.” (sahistory.org.za. Johannesburg is also known as the City of Gold, or eGoli in Zulu.)

PRINCE ALBERT: This small town in the Great Karoo had its own gold rush in the early 1890s.

The first nugget of gold discovered in the area was found in an aardvark’s burrow on the farm Spreeuwfontein, about 50 km from Prince Albert, in August 1871. The find prompted an official investigation, for which the Cape Government chose two of its finest: the roads engineer, Thomas Bain, and the surgeon and geologist, William Atherstone. Their report was unfavourable, though: they’d uncovered no auriferous (gold-bearing) rocks - or, as Atherston put it, the rocks of the area were all “too young” to produce significant amounts of gold.

In July 1891, though, a second nugget was found on the farm Klein Waterval, right next door to Spreeuwfontein. News of this find quickly got out, and at least 500 diggers had arrived and begun work on both farms by the beginning of August. In response, the Government proclaimed the diggings, and the prospectors began staking and registering a total of 1,042 claims.

The owner of Spreeuwfontein, Lodewyk Bothma, quickly erected a village with a hotel, two shops, and a post office on the farm. He called this village, ‘Gatsplaas’ in honour of the aardvark’s burrow from 20 years before. (Gat = hole; Plaas = farm).

Atherstone was right, though: the Spreeuwfontein goldfield ran out after only 504 ounces (14,288 grams) of gold were recovered,

By the end of 1892, both the village and the diggings had been abandoned.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s return to Knysna in the 1870s:

The Millwood Goldfields: a timeline

- 1876: First gold nugget in Knysna

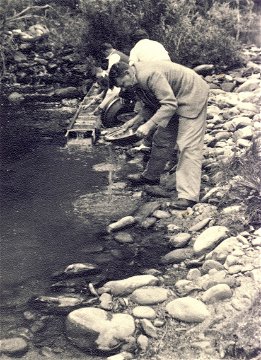

Searching for grit to feed his ostriches, James Hooper, of the farm Ruigtevlei (to the east of the Swartvlei Lagoon at Sedgefield), found a nugget of gold in the Karatara riverbed, at Karawater, between Sedgefield and Knysna. He needed the grit to feed his ostriches: the giant, flightless birds ingest it together with small pebbles and other particles to help their digestion.

Hooper is thought to have taken his find to William Groom, the pharmacist in Knysna, who tested the piece, and confirmed that it was, indeed, gold. It weighed 17 dwt (pennyweight), or around 26,4 grams.

Hooper then took the nugget to Charles F. Osborne, a government engineer who was encamped with 400 labourers at Swartvlei, where they were working on a new road between George and Knysna. Osborne sent the nugget to the Cape Government, which awarded £100 for further investigation. This capital allowed the pair to sink a 50-foot shaft at the site of the find, but it yielded nothing.

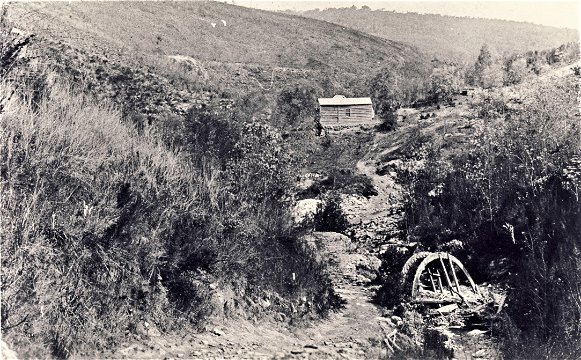

Nevertheless, Osborne continued prospecting in the rugged, almost inaccessible gullies and water courses of the region - particularly on the Karatara and Diep rivers - but he was forced to stop when the Government transferred him to work in Port Nolloth, on the West Coast. He never stopped dreaming of more gold in the forests, though, and would eventually return in 1885 to continue his search.

Once the news of Hooper’s find became common knowledge, though, prospectors began streaming into Knysna, and entering the forests illegally to search for gold.

- 1880: Mining commissioner

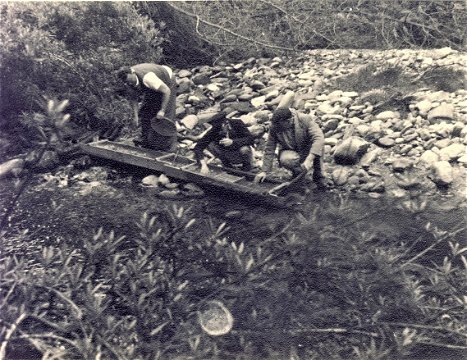

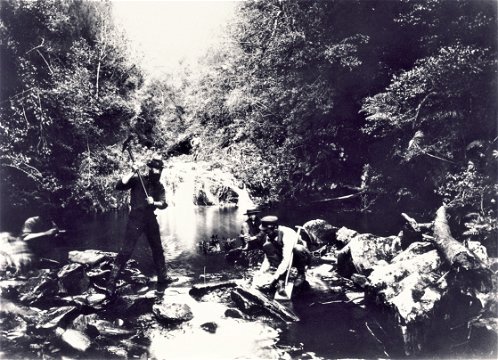

Official agents were also on the hunt, though, and in this year Thomas Kitto and the Cape Government geologist, E. J. Dunn, discovered alluvial gold in the area of Jubilee Creek. They reported favourably on the potential for mining in Knysna, and John Barrington, a son of the wealthy owner of Portland farm, Henry Barrington, was appointed mining commissioner for Knysna.

- 1883 Diggers committee

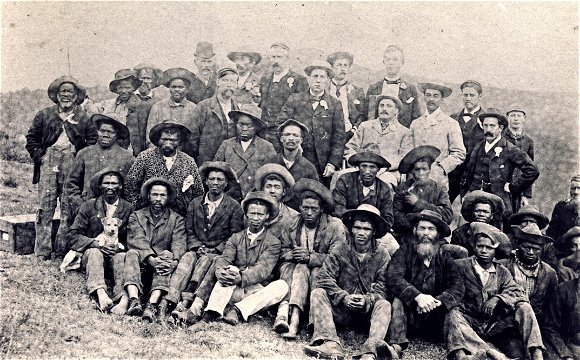

At around this time, as many as 200 prospectors from countries as far removed as Australia, California, and the UK (particularly Cornwall) were working in the forests. They formed a Diggers Committee to maintain law and order, and began lobbying for the proclamation of the diggings.

(1884: First significant gold finds on the Witwatersrand)

- 1885: Osborne’s half ounce

Osborne returned to Kysna, and to prospecting. His "reappearance in 1885 set up a further wave of optimism. His intensive prospecting campaign revealed a gold-bearing reef in an eastern tributary of the Karatara River. In five hours he and his party washed out at least half an ounce [14.2 grams] of gold. On 20 March 1885 he asked that the area be thrown open for pegging, and displayed an ounce of dust which he had recovered.” Winfred Tapson, Timber and Tides The story of Knysna and Plettenberg Bay, General Litho Ltd,. Johannesburg, 1967

- 1886: Digger dissatisfaction

By now Millwood was beginning to develop as a village, with its own newspapers - the Millwood Sluice Box was soon followed by the Millwood Eaglet and also the Millwood Critic - and formal buildings began to appear where only tents had existed before. These included four hotels, six shops, a committee room, and an agent’s office.

A post cart service was set up between Knysna and Millwood: it ran three times a week, with each trip taking on average five hours each way. The distance by road to Millwood was advertised as 29 miles (46,67 km).

The Government, though, had still not recognised the goldfields.

Tapson writes that the Government, “announced that all diggers on the Millwood goldfields were trespassers and warned them off. This gave rise to a concentrated fury that culminated in a mass meeting at George on the Market Square, to sound a protest. The government replied that no one was prohibited from digging, but that he did so at his own risk and secured no legal right until allotment was made under proclamation. The authorities were determined not to let in the rabble who would doubtless create chaos before the fields had been properly proved. An old Californian miner roared: 'They are making an enormous blunder. They are simply smothering the baby before it is born and killing the goose that might have laid gold eggs in due time!'

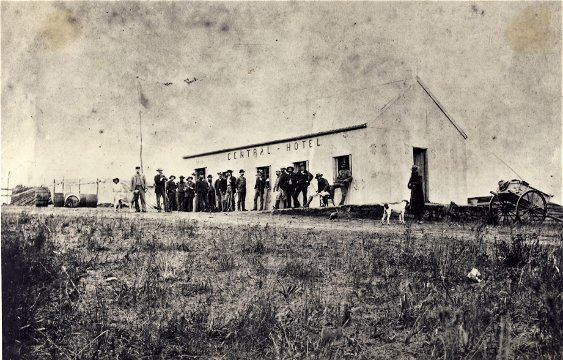

“The government remained adamant. On 13 December 1866—a day of unusual heat with the temperature at 105 degrees [40.5 Celsius]—a phalanx of diggers gathered in Millwood to impress upon the government the absolute necessity of extending the proclamation of the Precious Stones & Minerals Act over the reserved area of Millwood. About 350 men assembled in the large marquee outside Tom Young's Central Hotel with the Knysna magistrate, Maximilian Jackson, in the chair. It was arranged that the meetings should last two days and include a detailed tour of inspection over the diggings. Many strangers had come from as far off as Cape Town and Kimberley.

“The day's heat turned at night to rain. A deluge fell upon the tented concourse and never ceased throughout the visitation. All Millwood was turned to mud. In the end, the government capitulated.” (Winifred Tapson, ibid.)

- 1887: Millwood goldfields proclaimed

Tapson continues: “On 6 January 1887 the Millwood area was thrown open to all comers and Patrick Fletcher appointed Inspector of Mines. J. J. Hooper was convinced that this move helped to sound the death-knell of the goldfields. 'It was the greatest blunder when the diggers insisted on the government proclaiming the Mining Act. Before that the Diggers' Committee managed all amicably, with a nominal licence fee of 1s. per claim per mensem, but the government exacted a 10s. monthly fee, with a management and staff, etc. Had the first 500 to 600 prospectors been left in peace to carry on their work for six or twelve months longer, some at least of the hidden treasures would have been unearthed.'” (Tapson, ibid.)

On the 20th of June, 1887, Jubilee Creek was named in honour of the jubilee anniversary of the ascent to the throne in 1837 of the United Kingdom's Queen Victoria.

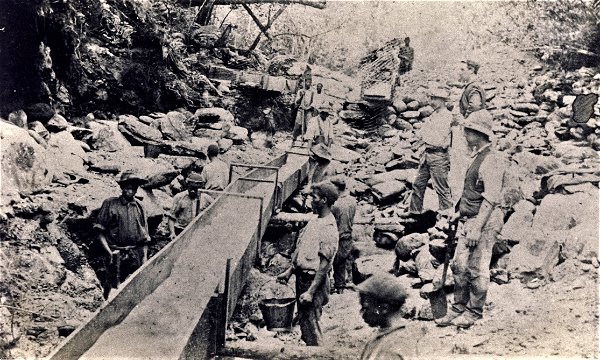

The official record of production for 1887 at Millwood was 655 ounces (18,568.938 grams) of gold.

- 1888: Decline

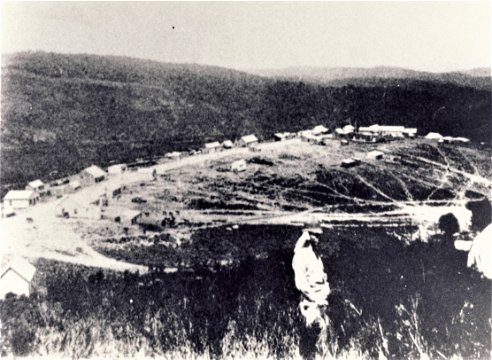

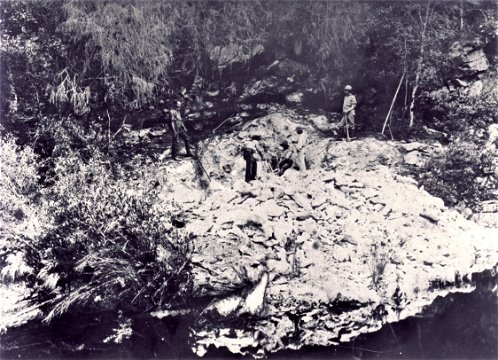

By the beginning of 1888, gold had been found in quartz veins on at least forty of Millwood’s registered claims. The economy was booming, with the goldfields boasting around 1,000 inhabitants - around 400 of whom were living in the village of Millwood itself.

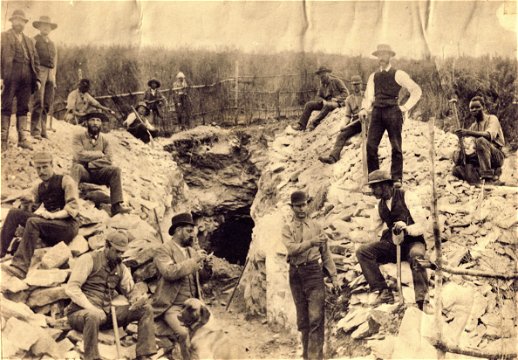

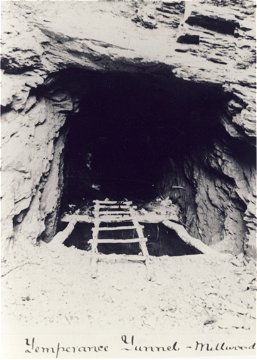

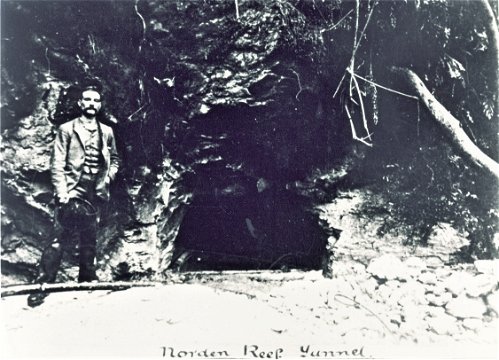

The diggings included the Bendigo Mine - whose “tunnel had gold all over it and its walls glistened with gold in the lamplight” (Tapson, ibid.) - and some of the more successful outfits had begun to import heavy industrial machinery. These included the Oudtshoorn Syndicate, which was operating a ten-stamp battery at Golden Gully, and the Cortney-Pioneer group with its 5-stamp battery.

By the end of the first quarter of 1888, though, it was becoming clear to everyone that all was not well with mining at Millwood, and by May both the shaft diggings and the alluvial finds were yielding almost nothing. The diggers and businesspeople began to drift away, with many looking for richer pickings on the Witwatersrand.

- 1889: Convict labour proposed

In this year, a convict station was set up to build the Phantom Pass, which had been designed by the famous roads builder and District Inspector of Works, Thomas Bain. Bain had retired by this time, and the roads engineer, Robert Bromley, was working with a team of prisoners on the project. The people of Knysna petitioned the Prime Minister of the Cape, Cecil John Rhodes, to use this convict labour to reopen the Millwood goldfields. As justification for their plea, they asserted that the Government Treasury had already received at least £14,663 (excluding taxes on hotels and shops) from the diggings, and that the total registered value of the gold recovered was £11,020.

Rhodes, however, was not interested.

The last of the diggers, shopkeepers, officials and hangers-on drifted away, and the Millwood Goldfields fell silent.

- 1924: Abandonment

The Millwood Goldfields were officially abandoned on 21 November by Government Proclamation No. 294/1924.

- Postscript: C.F. Osborne

“Poor Osborne, who had done so much to prove the goldfields, was suffering grievous hardships now (1888). The money, time and labour he had spent throughout these years were wasted. His family was reduced to poverty. A petition was drawn up by his friend drawing the government's attention to his plight.

“The government promised him a reward of £1,000 when he had recovered 3,000 ozs. In 1889, when illness and distress had beset him, he was awarded £200 on the condition that he renounced the right to any future claim. He was forced to accept this on account of unfortunate circumstances, but on the understanding that he was not debarred from appealing to the House.

“By the end of May 1892, Osborne had registered 2,360 ozs. of gold, and he was prepared to prove that more than the balance had been taken away by individual diggers and not registered. He appealed to Parliament for redress but only seven members voted in his favour. He was left a very bitter man indeed, although up to his dying day he never lost his faith in Millwood.” (Tapson, ibid.)

- Postscript: The name Millwood

The name ‘Millwood’ was given to the area well before the discovery of gold - when C.F. Osborne was employed to open a sawmill there for the Knysna-based timber merchants, Thesen & Co.

The project included the construction of a dedicated mule pathway (the sawn timber was tied to mules for transportation), which ran from the mill up to the track on the crest of the southern ridge.

A section of this pathway is still in use as part of the Outeniqua Hiking Trail.

Visit Millwood House

Millwood House - on the corner of Queen & Clyde streets in Knysna - was moved to its present position from its original site in the Village of Millwood after the village of Millwood was abandoned. It's now part of the Knysna Museum.

Visit the Millwood Goldfields (Goudveld)

The abandoned Millwood Goldfields are situated in the Goudveld (Jubilee Creek) area of the Knysna section of the Garden Route National Park. Attractions include picnic sites, walks, and MTB trails.

Visit the Garden Route National Park online

Author

This article was written for the Knysna Museum by Martin Hatchuel.

Share This Page